One Hundred Years Of Local History

J. Reynolds & W.F. Baines, 1978

The Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society 1878-1978

Written to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the establishment in Bradford of a learned Society for the study of local history and antiquities.

Four founder members who contributed greatly to the early success of the Society (These photographs formed the frontispiece of the original publication.)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance and encouragement they have received from many members of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society. Particular mention should be made of our President, John G.B. Haigh, for suggesting alterations and for valuable time he has given to the project. Thanks also go to Edwin Mitchell, who assisted in providing the photographs of the founders used in the frontispiece, and especially to Philip S. Bentham for the pen and ink drawings of the Bradford buildings reproduced in this book. Acknowledgement is given to the Metropolitan Bradford Library for the loan of and permission to reproduce the photograph of William Scruton. Thanks are due to the staff in the Local History Section of the Library, and to those in the Archives department for the assistance they have readily given. Finally, Mrs. Sheila Hodge has to be thanked for so very willingly undertaking the task of typing the manuscript in readiness for the printer.

Introduction

Learned societies have long had an honoured place in the history of European education and culture. In scope, they have taken in the whole range of intellectual experience and activity - the natural sciences, philosophy, literature, art, history, and more recently the social sciences.

In the days before specialisation and the professionalisation of knowledge, such societies brought together men and women of similar interests, and stimulated the research work which many of their members undertook. They provided a forum for the discussion of common problems. They maintained libraries and museums, and, above all, through lectures and the publication of their transactions and other records, they made a wealth of learning available to the educated public.

The earliest of the modern learned societies were established in Italy and France during the Renaissance of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In England, the Royal Society for the study of natural philosophy was founded between 1660 and 1662. The practice of organising learning in this way spread rapidly during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries - sustained by the increase in the number and size of the learned professions. The Royal Society of Arts, for example, was founded in 1753, the Royal Geographical Society in 1830; in the field of historical studies, the Society of Antiquaries dates from 1707, the Royal Historical Society from 1868. Societies such as these brought together new professionals and gifted and interested amateurs throughout the country and were to become part of the recognised structure of higher education and learning.

Local societies, operating in a similar variety of fields and under many different titles, have sometimes had a more transient career; but many of them have a long and impressive record of contributions to the cultural life of the areas in which they are located. The Yorkshire Archaeological Society (1863), the Surtees Society (1835), the Chetham Society founded in Manchester in 1843, the Manchester Record Society, the Halifax Antiquarian Society and the Thoresby Society have all been of particular importance for the study of northern history.

The Social Environment in Bradford

In Bradford, it was after the middle of the nineteenth century that conditions developed to give positive encouragement to such activities, for in these years the town started to take on a recognisable identity as a modern industrial city. In the first half of the century, Bradford was in the throes of an industrial revolution, and the fastest growing town in Europe. It became a 'world of strangers', for half its population were first generation immigrants - a few from Germany, some from Scotland, a great many from Ireland and the great majority from other parts of Yorkshire and the neighbouring counties. Almost all of them came from rural rather than city backgrounds. As inhabitants of a new world, they were principally concerned with problems of economic security, personal adjustment, and the development of the social controls needed to contain both the rape of the environment and the level of street violence which characterised the years between 1830 and 1850.

By the 1860's, however, the major industries had been established: the town had become the acknowledged centre of an international empire in worsted textiles. The old parochial and manorial administration had been replaced by the corporate institutions of a new municipal borough. When (at a price), the Ladies of the Manor had surrendered their privileged, feudal and financial interest in the local markets, few regretted the extinction of this remnant of manorial control. The fierce party battle about the existence and the authority of the new Corporation which had replaced the old order was over. The idea that, in matters which concerned the welfare of the borough as a whole, public good should prevail over private advantage was becoming more familiar and more generally accepted. Nobody liked paying rates, but the need for public expenditure to civilise the excesses of industrialisation, and to contain the selfcentred pursuit of profit had to be conceded. Thus, despite a fierce rearguard action by the 'economy-minded', the Beck was culverted and a main sewer system started the basic problems of urban engineering were being tackled. The police force was becoming a respectable and respected local institution. At a more personal level, coherent neighbourhoods were being created allover the town; and churches, chapels, friendly and improvement societies, temperance organisations, trade unions, political associations, social and sporting clubs were breaking down the anonymity of the new urban experiment. No longer did Bradford seem so much like a frontier town of the American Middle West, which well-brought-up women hesitated to enter on their own; it was taking shape as an organised community.

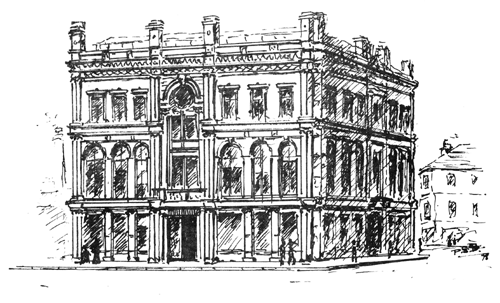

The embellishment of the city centre - an advertisement to impress potential customers and at the same time a demonstration of what the new community had achieved - went on apace after 1860. Old landmarks and the reminders of a quieter semi-rural past were disappearing - the Manor House in Kirkgate, by now a somewhat seedy Temperance Hotel; the delapidated Corn Mills in Aldermanbury; the Piece Hall1, which had been divided into shops for twenty years; the Bowling Green Inn, a good deal less important now that the coaching days were over. Old industrial development like Cliff's Foundry, the Canal Basin and the Union Street Mill, once the headquarters of Sir Titus Salt's alpaca empire, gave way to railways, warehouses and new thoroughfares. Merchants and bankers discharged their obligations to the developing city consciousness with handsome buildings in Little Germany and in the triangle of Bank Street, Kirkgate and Hustlergate. Malodorous slums in and near the city centre were demolished and new streets - Godwin Street, Sunbridge Road and Grattan Road - let in the light and air. Darley Street with the new Kirkgate Market and Free Library, and the Friends Provident Institution just above Godwin Street was, according to James Burnley, taking on 'a classical character' and becoming 'par excellence, the fashionable town thoroughfare'. Market Street, fast replacing the old medieval complex of Ivegate-Westgate-Kirkgate as the focus for the town's principle activities, lifted Burnley to heights of eloquence. With the new Town Hall, hinting of Florence and Siena, the Swan Arcade (successor to the old White Swan Inn), and the Victorian-Venetian Wool Exchange, it was 'so brand new and so imposing as to seem like a Metropolitan thoroughfare grafted on to the ancient street system'. In certain lights, when the twilight of the dusk obscured some of the unreconstructed corners of the area, you might imagine yourself 'in some stately Continental city'. The city centre which we associate with Bradford's hey-day was being put together in these years.

Although Bradford had remained in essence a working class town and the wealthy manufacturers tended to live outside the range of their own factory smoke, it had also become the home of a prosperous and energetic middle class, managers and executives of commerce and industry, members of the expanding professions, doctors, solicitors, accountants, engineers, journalists and school teachers whose number doubled between 1860 and 1880.

From South West to North East of the town, the old field patterns of Horton and Manningham were disappearing under enclosed garden squares, sumptuous villas, and rows of comfortable terraced houses built to meet the needs of this new middle class. The educational and cultural facilities available to them were also being reorganised; the new Bradford Grammar School was founded in 1871 from the alliance of Jacob Behrens' City High School and the old school foundation. The new Mechanics Institute was opened in Tyrrel Street in 1872 and the new Church Institute on North Parade in 1873. The Yorkshire College of Science (the Leeds University of the future) was well supported locally and the Technical College developed between 1878 and 1882. The number and variety of newspapers published in the town increased. The Bradford Daily Telegraph, The Bradford Times, and the Chronicle and Mail all began publication and the Bradford Observer became a daily paper. Two literary journals, the Yorkshireman and the Yorkshire Magazine, also appeared and were able for some time to maintain a high level of literary output.

Learned Societies in Bradford

As early as 1774, the Bradford Literary and Library Society had given the thriving eighteenth century township its niche in the cultural history of the time. By the 1850's successful musical societies were burgeoning from the grafting of the sophisticated musical enthusiasms of German merchants on the firmly rooted West Riding tradition of choral singing.

After 1860, cultural organisations with more directly educational aims began to assume a greater significance. The Philosophical Society (which had flourished briefly in the early forties under the leadership of Mr. Sharp, the Senior Surgeon at the Bradford Infirmary, and the Rev. W. Scoresby) took on a new lease of life. Its revival was supported by the wealthy upper-middle classes - business and professional men like Titus Salt and his sons, Henry Ripley, Matthew Thompson, Jacob Behrens, Dr J.H. Bell, civil engineer J. McLandsborough and William George a solicitor. It had a large membership and accepted women as associate members. A library and a museum were organised. To occupy the vacuum which existed before the opening of the Technical College the committee ran the first organised and laboratory-based science classes in the town. The programme of lectures included men of the stature of Matthew Arnold and T.H. Huxley; its activities gave the Bradford scientist Louis Miall (first Professor of Biology at the Yorkshire College of Science) the opportunity to establish his widely recognised reputation; by 1873, it was sufficiently distinguished to act as host to the British Association. Other societies also came into existence. The Arts Society was founded in 1869 under the chairmanship of J. Sowden, mentor of W. Rothenstein. The Scientific Association, the Naturalist Society and the Literary Club followed in 1875. In 1878, the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society was founded.

The Beginning of Local History Studies in Bradford

The subject of Bradford's history had first attracted the attention of John James in the eighteen thirties. His initial researches had made so little stir that, apart from Henry Leah (wealthy ironmaster) and one or two other local gentlemen, he had been unable to get together a list of subscribers. 'I have not printed', he wrote in the preface to his History and Topography of Bradford (1841),'a list of subscribers, because I early discovered that I should not meet with encouragement by subscription, and determined to rest the success of the work on the sale after being published.' Twenty years later, attitudes were changing; the rapidity with which the structure of the town was being altered confronted Bradfordians sharply with the disappearance of a part of their own past. The textile manufacturers had actually commissioned James' History of the Worsted Manufacture, and when he issued his Continuation and Additions to the History of Bradford and its Parish (1866), he was able to thank his subscribers warmly for their generosity.

Every student of Bradford's local history has a debt to pay to the memory of John James. His connection with the beginnings of the Historical and Antiquarian Society, though not direct, is also clear. He was the most distinguished member of a group of writers who met regularly at Tom Nicholson's dining room in Kirkgate, and at Abraham Holroyd's bookshop in Westgate in the late fifties and early sixties. Among his companions were poets like Stephen Fawcett, James Waddington, the Saltaire woolsorter and Ben Preston, the dialect poet. Younger historians - William Scruton and William Cudworth also met there and derived encouragement and inspiration from the successes and the conversation of John James.

Abraham Holroyd himself did much to inspire early studies in local history. He had, in effect, provided the setting for the first embryonic 'learned society' in Bradford, at a time when there was neither public museum, free library, philosophical society, nor historical society. He had started a journal, the Bradfordian published for two years between 1860 and 1862, to give local writers an easier outlet to the public. He was himself an enthusiastic local historian. He had assisted the Rev. Baring-Gould in researches on Yorkshire folk customs, and his own Colleateana Bradfordiana came out in 1873. An American scholar, Martha Vicinius, in her book The Industrial Muse (1974) has described his work as 'vital to the development of the culture of Bradford'.

A growing interest in Bradford's past was reflected in the columns of the local press. Regular letters from Vetus and Sexenarian in the Bradford Observer recalled the days when Dicky Hodgson hunted the hare and the fox with his pack of hounds across from Wheatley Hill to Heaton Shay, when the Bowling Green became a bustle of activity as the Defiance arrived at 8 o'clock in the morning, and the days when the inhabitants knew everybody they were likely to see in a morning's walk along Kirkgate. In 1868 William Cudworth now a journalist with the Bradford Observer published his Historiaal Notes on the Bradford Corporation, and began a regular series of articles in the Observer under the title of Round about Bradford. They have remained an immense store of local historical material. In February, 1874, he also started a weekly column, Notes and Queries, devoted to matters of local historical interest. Its contributors included most of those who were to become founder members of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society; in particular T.T. Empsall, a local businessman, comfortable but not wealthy - for whom the Public Record Office was already something of a second home - Joseph Horsfall Turner, the Idle schoolmaster, and the William Scruton mentioned earlier who, like John James before him, had worked for many years in a Bradford solicitor's office.

The Origins of the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society

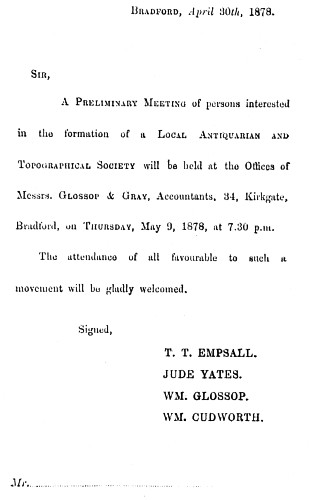

Early in 1878, T.T. Empsall appears to have opened up with William Cudworth the question of starting an historical and antiquarian society to give pattern and purpose to their work. Shortly afterwards, along with Jude Yates (of the Post Office) and William Glossop (an accountant) they issued an advertisement announcing a meeting to consider the propriety of forming a local antiquarian society. The meeting was held an May 9th. 1878, in the offices of Messrs. Glossop and Gray, Mann's Court, Kirkgate. It was attended by E.P. Peterson, F.S.A., an architect who had recently set up in business in the town, C.G. Virgo, the librarian in charge of Darley Street Free Library, W. Greaves, a solicitor, W.M. Gray, Glossop's partner, Dr Maffey, medical practitioner, George Brewer, William Scruton and J.H. Turner along with the convenors. The resolution, proposed by E.P. Peterson and seconded by J.H. Turner,

that an Association to be called the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society be formed

was carried. T.T. Empsall was elected President, William Cudworth became secretary and William Glossop, treasurer. Subscriptions were fixed, for the time being, at five shillings a year, and a subcommittee was appointed to formulate a code of rules and to find a suitable meeting place.

The meeting reconvened three weeks later at the Globe Hotel, Piccadilly. Thirty-five members were enrolled and Mr. Fairless Barber, F.S.A., one of the secretaries of the Yorkshire Archaeological Society, was invited 'to make practical suggestions about a future programme'. He suggested that the manorial records should be examined and emphasised the urgent need to record the recent history of Bradford. He would, he said, also like to see written up the history of each of the local churches and chapels and recommended that the society should start immediately to maintain a pictorial and photographic record of the Bradford which was fast disappearing. After his speech, the code of rules was discussed, a few amendments made, and the meeting adjourned to June 22nd, again at the Globe Hotel.

At this meeting, the structure of the new society was confirmed. The code of rules was accepted. E.P. Peterson became Vice-President, and William Scruton was appointed Curator and Librarian. Dr. Maffey, J.H. Turner, John Thornton and C.G. Virgo joined the already appointed executive officers to form the first Council of the society. The first official act of the new society was to pay its debt to Abraham Holroyd. He was now in retirement at Eldwick and could not be expected to play an active part in their work. He was therefore elected an honorary member 'in consideration of the many services rendered ... in furthering the objects contemplated by the Society'. The Library also received its first contribution when John Thornton donated a map of Bradford by Walker and Virr, dated 1873,

The Early Activities of the Society

The first business meeting of the Society - its formal inauguration - took place at the Globe Hotel in the evening of July 12th, 1878. Eighteen were there - all men. T.T. Empsall in the chair, S.O. Bailey, the lithographer, S. Butterworth, W. Cudworth, W. Chettle, W. Gray, W. Glossop, Dr. Maffey, Sam Margerison, a Calverley timber merchant, E.P. Peterson, John Thornton, J.H. Turner, J. Whitehead, and Jude Yates. Empsall, as President, gave the inaugural address and defined their objectives as he saw them. He assumed without question that they would constitute a working society, a voluntary research team in which most of the members would be actively involved. He indicated some of the tasks which awaited them: examining and recording the many documents relating to pre-industrial Bradford which were located in the Public Record Office, the British (Museum) Library, and the House of Lords: making more easily available the manuscript collections in private hands; recovering the administrative records of the parish and township, for their whereabouts was then unknown: transcribing the parish registers of baptisms, burials and marriages: and compiling biographical accounts of important inhabitants (past and present) connected with the area. He also indicated that the society would have to engage in the battle for conservation. Already, important monuments and buildings were not only being allowed to decay but were being actively despoiled and desecrated. Intervention was a matter of urgency.

A programme of lectures and excursions was also organised. Messrs. Peterson, Bailey and Yates undertook to prepare an illustrated talk on the Paper Hall (already the object of conservationist regard). J.H. Turner offered to give a lecture on 'Old Eccleshill' at the next meeting. In December, William Scruton spoke to the Society for the first time. His analysis of the Johnson Map of 1801 and the Atkinson plan of 1825, reported in the Transactions of the Society, still makes fascinating reading. Visits to Kirkstall Abbey, the Thornton Valley and the Pudsey-Fulneck district were also proposed. Excursions and lectures such as these were primarily intended to support the practical work of the society, and tended perhaps to be under-rated by some of the more austere and dedicated of researchers. They were, however, an important element in the work of the society - for they enabled the researchers to reach wider audiences than had been possible through the informal meetings at Nicholson's Dining Room, and Abraham Holroyd's shop in Westgate. They also added to the cultural and educational facilities of the town, providing outlets for people who wanted the means of intelligent relaxation in congenial association with men and women of similar interest.

In the first year and a half, to the end of 1879, a good deal was accomplished. The objectives of the society were defined and published in the following terms:

- the examination and reproduction of documents and records bearing on the past and present history of the locality.

- the searching and transcription of ecclesiastical or public records, registers, etc.

- the preparation of plans and views of places or buildings of interest or antiquity, or other objects that it may be considered desirable to preserve.

- the collection of antiquities, books, coins, etc., especially those associated with Bradford or its neighbourhood.

- the preparation of papers on ancient or modern institutions.

- the study of architecture so far as it lies within the scope of the Society's operations.

- the preparation of biographical and genealogical notices of local worthies and the preservation of portraits.

- the collecting of materials relating to the traditions, manners and customs of the town and neighbourhood, and generally the furthering of the collection and preservation of whatever may be considered of historical and antiquarian interest illustrative of the history and topography of the area covered by the society.

A start was also made with carrying them out. A number of maps, portraits and pamphlets were collected to form the nucleus of the library and what was intended to be a small Historical and Antiquarian Museum. Several of the members began to compile the bibliography of books relating to Bradford and district. Arrangements for the publication of the journal of the society, The Bradford Antiquary, were almost completed. T.T. Empsall obtained a copy of the Bradford Parish Registers and initiated the transcriptions which were eventually to be printed in full. The society also considered two conservation problems. At a thinly attended meeting, the question of the Thornton Old Church was discussed and a slight majority sustained a resolution supporting its preservation. (Surprisingly, William Cudworth voted against the proposition). A lengthy and vigorous campaign was also conducted to save the old Haworth Parish Church with its important Bronte connections. Unfortunately, it had very little local support and failed. Fourteen papers were read at the monthly meetings - all by members of the Society. They were all concerned with current research and included accounts of work being done by those men who were to be the mainstay of the programme for the next two decades, T.T. Empsall, W. Cudworth, J. Horsfall Turner, W. Scruton and rather less well known members like Sam Margerison and Simeon Rayner. Twelve excursions were held and these proved very popular indeed. With a membership which had grown from 75 at the end of 1878 to 89 at the end of 1879, the Society had clearly covered its costs comfortably and had a balance in hand of £10.5s.9d.

In the next decade or so, the practical problems of organisation were tackled and as far as possible resolved. In its first year, the Executive Council was made up of the officers and four elected members. This was quickly recognised to be too small a body to cover the growing interests and responsibilities of the Society. After some experimenting with the number of elected members, the figure was eventually settled at twelve. A system of formal balloting was also introduced as the society grew in size. The officers of the Society generally served for considerable periods of time. T.T. Empsall was President from 1878 until his death in 1896, except for one year (1882-3), when the banker George Ackroyd was President. William Glossop was treasurer from 1880 until his death in 1908. William Cudworth began in l878 as corresponding secretary, became editorial secretary in 188l and held the post untill893. Thomas Howard was corresponding secretary from October l894 to October 1910. It was estimated that he attended nearly 300 meetings and other functions, 74 excursions, and had sent out over 25,000 letters and circulars in that time. The most prominent members of the council in those years included S.O. Bailey, A.D. Sewell, J.W. Turner, William Scruton, H. Gaskarth, C.G. Virgo, Butler Wood, C.A. Federer, William Claridge and John Clapham (who for many years after 1885 was also an energetic and enthusiastic secretary). The Vice-Presidents included S.O. Bailey, S. Margerison, William Thackray and John Lister of Shibden Hall.

The question of the subscription provided something of a problem. At first it was fixed at five shillings. Almost immediately, some wanted to raise it to ten shillings, in order, as it was said, 'to give the Society greater status'. Eventually, in 1891, it was raised to seven shillings so that each member could be provided with a copy of The Bradford Antiquary, which had appeared for the first time ten years earlier.

The Meeting Places of the Society

The most important problem, the provision of a suitable meeting place, caused a good deal of anxiety, particularly as the collection of materials and books began to grow into a substantial library. Ideally, the members would have preferred their own rooms, properly equipped for library, museum, lectures, discussions and council meetings. For a short period in the l890's three rooms were rented in Leeds Road, but the income of the society never permitted much extravagance in this direction. The earliest council meetings continued to be held in Mr. Glossop's offices in Mann's Court. Subsequently they seem to have been held wherever it was convenient, the Church Institute, the Darley Street Library, the Liberal Club, and frequently in one of the hotels of the town. The Church Institute in North Parade was used at first for the regular monthly meetings. Then, in September 1878, Dr. Keeling, the Headmaster of the Grammar School, gave permission for the use of a room in the school in Manor Row. In 1883, it was decided that accommodation in the Darley Street Library was more suitable since proper arrangements for the Library and the exhibits could be made there. Shortly afterwards, the Philosophical Society offered to share its accommodation in Sunbridge Road. The suggestion arose out of a nation-wide movement to unify the work of learned societies in the main centres of population. In 1883, the British Association appointed a committee to induce local societies to group themselves around sub-centres for the interchange of information and to spread the cost of publishing the results of their research. The Mayor of Bradford took the matter up and called a meeting of the various organisations to discuss the possibilities of a type of federal structure. Most of the societies, however, wanted to preserve their basic independence. They opened their meetings to each other's members on a reciprocal basis and published a common programme, (a kind of 'What's on in Bradford'), but the principal consequence was that for a time the premises of the Philosophical Society became the common meeting place. As far as the Historical and Antiquarian Society was concerned, this arrangement lasted from 1885 to 1890. The Society then returned first to the Darley Street Library, and then to the Church Institute. Finally, it settled at the Mechanics Institute, where, by 1917, owing to the expansion of municipal facilities for education, the accommodation was under-utilised and where the lecture rooms had recently been re-organised in such a way as to make them more suitable for the Society's activities. It remained there until the destruction of the building in 1972.

Developments until 1911

Connexions were established with other antiquarian and historical societies. Speakers and publications were exchanged with the Yorkshire Archaeological Society, the Surtees Society, and the Society of Antiquaries, among others. Help was given with the establishment of the Thoresby Society in Leeds.

The membership of the society continued to grow until just before the First World War. For several years after 1880 it hovered around 110, a figure it maintained until the beginning of the new century. After that membership began to fall away a little. Unlike the Philosophical Society, it was not a fashionable meeting place for the elite of Bradford's textile community. Though a number of prominent citizens were always members, the society drew mainly from the solid middle class, the smaller manufacturers, the self-employed business men and members of the professional and administrative groups whose numbers were rapidly increasing in Bradford at the end of the nineteenth century. As early as November 1883, there were twelve solicitors, eight doctors and surgeons, and twelve men connected with banking and accountancy in the 118 members. There were also a dozen schoolmasters, a number of local government officials like Mr. Virgo, the City Librarian, and a group of architects, surveyors and others connected with the construction industries. Several came from outside Bradford: Sam Margerison came from Calverley, John Lister from Halifax and Simeon Rayner from Pudsey, for the society was for some years the only one of its kind in the locality, and Bradford, in any case, was rapidly becoming the metropolitan centre of the West Riding textile area. There were, however, no women members in the earliest years: presumably they attended the Society's functions as guests of husbands, fathers and friends. It is not until the beginning of the 20th century that a few begin to be named as members in their own right. Of all the Society's activities, the excursions attracted the most popular support. The report for 1885 reads:

The excursions this year were more numerous and better attended than they have been ever before. This branch of the Society's work is not only popular but is very useful in opening the eyes of the members to the vast amount of unexplored Antiquarian and Historical matter that lies at our own door.

It seems in fact that they quickly became a familiar and welcome addition to the social life of the town. The earliest excursions naturally concentrated on places of interest in the locality, but within two or three years members and their friends were being taken to almost every part of Northern England. By the 1880's parties of over 100 men and women were common. Eighty people took part in the first excursion of the l887 session. They went to the two Riddlesden Halls, Cliffe Castle and Keighley Church on the Saturday afternoon of May 14th. The main party left Bradford in reserved carriages on the 2.18 Midland train. Some joined the expedition at the Manningham, Frizinghall and Saltaire stations, and others drove over by carriage or tricycle. Mr. Briggs read part of a paper on East Riddlesden Hall on the lawn in front of the house. The party crossed the River Aire by boat to Cliffe Castle, where those members of the Society who had visited the Louvre, and Normanhurst, the celebrated place of Lord Brassey in Sussex, made favourable comparisons and 'were delighted with the taste displayed in the conservatories and the magnificently decorated rooms and library'. At the end of the day 'the party... adjourned to the Acorn Coffee Tavern where an excellent meat tea, the menu of which consisted of sirloin of beef, ham, tongue, veal and ham pies, sweets etc., was provided, to which members did ample justice'. Mr. Briggs completed his paper on Riddlesden Hall and the party returned to Bradford. It had cost those who went by train two shillings and sixpence.

A visit to Pontefract Castle and district, made by 125 men and women in July 1889, finished in even more sumptuous fashion at the residence of Mr. & Mrs. Tew of Carlton Grange, Pontefract.

Mr. Tew then conducted the party into the grounds where on the spacious lawn in front of the house a photograph was taken, by Mr. Hepworth of Brighouse, of as many of the company as could be got together. Tennis, cigars, etc., were then introduced and to the strains of the band of the 3rd Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment (which under the conductorship of Bandmaster Craven, had discoursed sweet music during the consumption of the repast) the time was very pleasantly passed until 8.30 when, after a most pleasant afternoon, the party was re-conveyed to Pontefract Station (in horse wagonettes) to start at nine o'clock on the return to Bradford

William Scruton, William Cudworth and one or two others were not altogether happy at this marriage of instruction and pleasure. Scruton, on one occasion, doubted whether enough attention was being given to the 'real business of the Society': and when a large party visited Isaac Holden's splendid mansion at Oakworth, Cudworth, while applauding the hospitality and admiring the establishment, commented austerely that it was hardly of antiquarian interest.

In fact, the Society was always rather more than an unofficial research team. It fulfilled a valuable social function as well as contributing to the educational and cultural life of the town, and this function was always implicitly and sometimes explicitly recognised. The Annual General Meeting was enlivened with some type of social entertainment - the conversazioni or soiree characteristic of Victorian society; and eventually the annual dinner. It became the tradition for the President to entertain the members of the Council to tea at the Liberal Club or the Conservative Club (according to taste) or in one of the hotels - the Victoria, the Royal or the Alexandra. John Clapham, in his year of office, offered hospitality at Morecambe. Occasionally, when prominent members were married, the Society gave a wedding present and it was always meticulously ready to sympathise with the families of members who were ill or who had died. The impression left by the written record of these days is that it was not only an active historical and antiquarian Society; it was also a very good club.

The lecture programme never, in these years, attracted the same degree of popular support as the excursions. For a good many years, an audience of between thirty and forty was exceptionally good; the average attendance seems to have been between twenty and twenty five. It was also something of a problem to maintain the comparatively heavy programme - and indeed for a period just before the 1st World War the number of lectures was reduced to six. A great deal of the work fell on a small number of members actively engaged in investigation and in writing - none of whom, however, seems to have complained about the regularity with which they were given the opportunity to present their work to a public audience. Nor was it perhaps so important that attendances were relatively small. The proceedings of the society were regularly reported in The Bradford Observer and The Chronicle and Mail and so were made available to a much larger number of people.

The lectures covered a wide field of interests and maintained a remarkably high standard over the years. They naturally reflected the interests of the principal members. In the earlier years, they were concentrated almost exclusively on the history of the locality, for the researchers were interested in disentangling the roots of the new world they lived in and in recording the passing of a way of life they remembered, perhaps with affection, from their boyhood. Most of the themes they pursued were of immediate interest. When T.T. Empsall gave his lectures on medieval Bradford he was not talking about a long-forgotten world which nobody could really comprehend. He was describing the high days of a manorial system of which the last traces were just disappearing. Everybody in his audience would be acquainted with the idea of a manorial court, for one still met in Bradford although it had no effective power. They probably knew also that William Ferrand of St. Ives collected feudal dues in Thornton. Similarly, when William Cudworth lectured about the Soke Mills2 which had stood just above Aldermanbury for centuries, he was elucidating the origins of a controversy which had recently been settled. By 1870, the Corporation had, in effect, bought out the medieval rights of the Lady of the Manor to the monopoly of corn-milling in the central area of the Borough and so (in Cudworth's words) had 'virtually extinguished an ancient custom which had latterly grown into an acknowledged grievance'. The many discussions of local ecclesiastical history were often of crucial interest to men and women to whom the question of religious affiliation and the authority of the Church was the stuff of political controversy. William Scruton's famous lecture on the Great Strike of 1825 (quoted in many of the histories on the development of English society written in recent years) recalled the turbulent origins of Bradford's textile world; it was also an appropriate reminder of the persistent problems of industrial relations in a year which had just seen the conclusion of a bitter and protracted Dyers' strike.

Among the more interesting and immediately relevant of the lectures given in the early days was one given by Mr. J.W. Turner, entitled 'Some Old Bradford Firms'. In it he expressed what must have been for the time an unconventional point of view. He began by making a plea for the study of industrial and social history.

That branch of literature which its professors are pleased to term History, generally deals with what for want of abetter term, may be called the ornamental side of the life of the community. It dwells abundantly on the virtues or vices of Kings and of the follies and intrigues of Courts. It decorates its pages with the sanguinary achievements of soldiers, or it sings the praises of pious divines and learned lawyers, while the pioneers of the industrial arts and the collectors and distributors of the nation's wealth are left to pass into oblivion unhonoured and unsung ... It is evident that Historians and Antiquarians (have) ... too often treated them with silent contempt.

Then he proceeds to trace the fortunes of a number of firms which had been in business in the most important decade of Bradford's Industrial Revolution, 1831-1841, the decade which saw the development of alpaca and the widespread introduction of the power-loom. Among other things, he noted that of 227 firms he had been able to identify, only 56 still survived in business. 25 had 'retired with more or less of a competence', and no fewer than 146 had failed. The lecture was greeted with enthusiasm but unfortunately was never reproduced in The Bradford Antiquary.

Towards the end of the century, founder members died or became less active and there is some evidence to suggest that the earlier enthusiasms were beginning to wane. Bradford's middle class was becoming more cosmopolitan and men whose interests were less concentrated on the locality began to move into positions of influence. It was perhaps for this reason that the nature of the lecture programme was modified, though, happily, not fundamentally altered. Topics like 'The Primitive Lake Dwellers' given by Charles Federer, 'Roman Baths at Bath' by H. Wroot, Percival Ross's 'The Roman Wall', Dr J.H. Rowe's 'Anthropology of Yorkshire' (absorbing enough but not the product of primary research nor likely to stimulate it further) began to take their place in the list. Speakers from outside the society were also invited to speak on topics of general interest much more regularly than had been the case in the early pioneering days. These generally attracted large audiences - on one occasion, as many as seventy. On the other hand, the Bradford historian, Margaret Law, could only get twenty-one to listen to her on the local consequences of the Industrial Revolution.

The situation caused some people to express anxiety and to suggest that the surviving veterans - Lister, Scruton, Horsfall Turner and Margerison - should be persuaded to resume their active work in the Society. Yet, there was no deep cause for alarm. The central purpose was never obliterated; and several years before the 1st World War broke out there were clear indications of a resumption of interest in basic research of local importance. The Hemmingway manuscripts were examined and indexed. The Manor Court Rolls, rescued from oblivion, were being transcribed, and in 1911, the decision had been taken to proceed with the publication of a Local Records Series as soon as the financial situation allowed. A year later, The Bradford Antiquary had reached the fifth volume - the third of the second series. As a focus of informed opinion the Society was also using its influence and experience to good purpose. Its intervention had helped to preserve the records of Roman occupation at Ilkley. It had undertaken a survey of Celtic remains on Baildon Moors, and handed its report over to the corporation authorities when the area was acquired for public use in 1900. It had instigated the campaign which persuaded the Bradford Corporation to maintain Bolling Hall3 (recently abandoned by Bowling Iron Works) as a repository of local historical materials and records. It also played a part in the development of the University Extension Lectures programme started in Bradford towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Early Contributors in the Society's Work

Of all the men who had helped to establish the Society on its firm base, Thomas Thornton Empsall, first President, must be given pride of place. He was born in Brighouse and, as a young man, trained as a schoolmaster at Borough Road Training College in London. He returned to Bradford and after his marriage, began a small but successful textile business. Like many other members of the Society, his range of civic commitments and personal interests was extensive. He acted as Borough Auditor; he sat as a councillor for Listerhills Ward and, for a short time, was a member of the School Board. During the 1850s, as secretary to the Woolcombers' Emigration Aid Society, he played an important part in the resettlement of Bradford hand wool-combers whose livelihood had been destroyed by the progress of technology. As a historian contributing to the work of the Society, he was indefatigable. In addition to his transcriptions of the Parish registers, he spent long hours in the Public Record Office and other manuscript depositories tracking down important documentary evidence of Bradford's past. His lectures on medieval Bradford, printed in The Bradford Antiquary, remain, along with James's History and Topography of Bradford, the most useful sources of information for the period. They continue to stand up well against the most recent work of present-day scholars.

William Scruton and Joseph Horsfall Turner were perhaps less active in the routine work of the Society - they were not the easiest of men to work with, and occasionally withdrew - but their contributions to its principal objectives were outstanding. William Scruton was born in Horton Green in 1840 and died in 1924. For most of his life, he worked as a solicitor's clerk, an occupation which both facilitated and encouraged his insatiable curiousity about the past. He contributed regularly to the Antiquary, lectured frequently, and spent a great deal of time - for he was, among other things, a fine water-colourist - recording views of the Bradford which was disappearing before his eyes. He explained his motives in a lecture given to the Society.

While the great and rapid alterations that were being made in many parts of the town some years ago were in operation, it occurred to me that unless something was done and done without delay, to secure views of the principal places of interest, every trace of the same would be removed and the opportunity of preventing their utter annihilation gone for ever. With such ability as I possessed, I succeeded in taking views of many relics of historic interest, all traces of the existence of which might otherwise have been lost.

Among the many interesting views he recorded were the Old Corn Mill, the Old Cock Pit, Bradford Old Bank, the Old Piece Hall, the White Swan Inn and the Quaker Chapel at Goodmansend. Like any good local historian, he spent many hours browsing around the district; on one such ramble, he came across the ancient Baildon stocks embedded in the walls of a reservoir and saw to it that they were restored and placed where they now stand in the centre of the village. His first published work was the Birthplace of Charlotte Bronte (1884) and his most important contribution to the history of the locality, the well known Pen and Pencil Sketches of Old Bradford. In it he deployed the full range of his exhaustive knowledge and brought together a wealth of information about the leaders of Bradford society in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries - their activities, their families and the part they played in the development of the religious, political and social institutions of the town.

Joseph Horsfall Turner was born in Brighouse in 1845 and died in 1915. Like Empsall, he trained as a schoolmaster at Borough Road Training College and, in 1873, came to Idle, where he spent forty years in the service of education, and, in his later years, as a Justice of the Peace and an Urban District Councillor. He developed an international reputation as a genealogist. He was especially interested in the history of local Nonconformity. His most important work was an edition of Oliver Heywood's Diaries. For a number of years he was a member of the informal history and literary society which gathered around Abraham Holroyd. In addition to being a founder member of the Bradford Society, he had been associated with the beginnings of the Yorkshire Parish Register Society, the Yorkshire Archaeological Record Society, the Bronte Society, the East Riding Historical Society, the Halifax History Society and the Thoresby Society.

A group of younger men carried the work on into the inter-war years. They included Harry Speight4, assistant cashier at Bowling Dyeworks, to whose transcription of the Bradford Manor Court Rolls many present-day students are indebted. The drama of their discovery is concealed in the sober language of the minute secretary:

Mr. H. Speight mentioned the efforts he had made to discover the whereabouts of the Bradford Court Rolls. He reported that he had (eventually) made a direct appeal to Lord Mountgarret through the country steward of the Manor. (He had been granted) permission to inspect the rolls which turned out to be in excellent preservation, and beautifully written. Mr. Speight is now engaged in making extracts from them.

Butler Wood, Chief Librarian in Bradford until 1925 and William E. Preston, Director of the City Art Gallery and Museums until 1939, and a member from 1909 until his death in 1957, kept alive the connexion with the City Library service started by Charles Virgo at the beginning. They were joined by H.J. Maltby, also of the Library Service, who was Secretary from 1920 to 1926. William Claridge (1856-1929) in the midst of a busy public life in Bradford education and politics, also played an active part, serving on the Council for many years and holding the office of President in 1925. He found time, as well, to run a successful firm of accountants and to write the history of the Bradford Grammar School.

Of this group, however, Percival Ross (1858-1923) was probably the most outstanding contributor to the reputation of the society. A Bradford man, he was civil engineer and architect. He acted as Surveyor to the North Bierley Urban District Council until that area was incorporated into Bradford. He joined the Society as a young man and at various times acted as secretary, vice-president and president. His principal antiquarian interest lay in the field of Roman Britain; he was considered the most eminent authority on Roman walls and roads in the North of England - a reputation which brought him the distinguished honour of a Fellowship of the Society of Antiquaries. His interests are clearly reflected in the lectures, excursions and publications of the Society, between 1900 and 1920. He gave a number of talks on the old roads and bridges of the West Riding, led many excursions to Roman sites and along with a small group of Society members conducted at least one excavation of part of the Roman road across Otley Chevin. A minute of 1917 notes his work:

A joint excursion to the Roman fort at Slack near Huddersfield was undertaken on Saturday the 24th July by members of this Society... The party, numbering about fifty, was ably conducted by Mr. Ross who pointed out the most interesting features revealed by the excavation of these Roman remains.

The Inter-War Years

The pattern of the Society's activities did not alter substantially as a new generation of members took over between the two world wars. The excursions lost some of their popularity in the years immediately after the First World War, However, though the record is less precise than in earlier days about the quality of entertainment offered, it is clear that by 1926 they were once again among the most profitable of the Society's ventures. Journeys did not range much further afield despite the fact that a motor coach was brought into use in 1921. There was never a lack of interesting sites and other evidences of the past to examine, and, in earlier days, members had been eager to make use of the exciting possibilities of the new railway network. The journeys did tend to reflect the more general interests of the bulk of the Society's members. A typical programme was that approved for 1937. A day excursion was taken to Weaverthorpe, Thwing and Rudston. Half day excursions went to Lead and Saxton churches and Towton battlefield; Upper Wharfedale; Sheriff Hutton Castle and Church, Bulmer and Foster Churches; Kirkham Abbey and Bossall Church. Evening excursions included Wood Lane Hall, Sowerby, Kershaw House, Luddendenfoot; Otley Church and Prince Henry's Grammar School; and Tyersal Hall and Fulneck.

The lecture programme was maintained at an average of about ten a year. Here, undoubtedly, a tendency developed to range further afield. One year, the list included talks on 'Romance in the History of the Wool Trade', The Danby Family, Lindisfarne, Roman Yorkshire, Arthington Nunnery, the Historic Homes of England and a description of an Antiquarian's outing in the Vale of Mowbray, but contained nothing specifically concerned with the history of Bradford and its locality. Yet, such topics were not neglected. In one session Dr J. Hambley Rowe spoke about Francis Corker, the Fighting Parson of Bradford, and gave a fascinating lecture on the discovery in 1922 of Celtic remains - burial urns, food vessels and the bones of a female aged between 30 and 40 - in Chellow Dene. From 1927 onwards, Wilfrid Robertshaw regularly brought fresh local material before the Society - his work, for instance on the manorial systems and ownership patterns of Tong and Clayton, and his reconstruction of 17th century Manningham. Occasionally, an 'Old Bradford' evening was organised, and these, along with 'members' nights' set aside for the discussion of current work in the Society, ensured a steady flow of new ideas and material. A great deal of attention was being given both to local pre-history and to the 16th and 17th centuries. What is, nevertheless, noticeable in these years is the comparative lack of interest in the immediate past.

The organisation of the Society also remained much the same. Subscriptions were raised in 1920 from seven shillings to ten shillings and in 1927 junior membership at two shillings a year was instituted. In 1933, two new executive offices were created - the Excursions Secretary and the Lectures Secretary. It is also worth recording that in 1936 the first woman President, Miss H.F. Atack, A.L.A., was installed.

Membership had begun to fall off a little before the war - indeed in the Annual Report for 1911 the view was expressed that a membership of 129 was 'hardly worthy of a town the size of Bradford', and there was no improvement until after 1929. It is difficult to suggest reasons for this. Perhaps the increased subscription deterred some. It is also true that a number of the most prominent members died during the first two decades of the century - William Glossop, Charles Federer, second editor of The Bradford Antiquary, Harry Speight, Joseph Horsfall Turner, William Scruton, William Cudworth and John Clapham who had for many years after he had relinquished the post of secretary, acted as an efficient and enthusiastic 'de facto' excursions secretary. Butler Wood and H.J. Maltby also left the district in the early twenties. Perhaps, such men could not be easily and immediately replaced. Yet, although there was some delay in the publication of the Antiquary after the war, in most respects the Society was as active as ever. The explanation is probably a more general one. Local history seems to thrive best in periods of rapid change. Although these were the years when Bradford acquired its international reputation as the 'Mecca' of social reformers throughout the world, in a number of significant ways it was a dormant institution. Little if anything was being done to transform a city which had accumulated generations of grime and still lay regularly under a pall of yellow smoke, a city in which the beauty of the local stone had been long obliterated. Population was, if anything, diminishing; the textile trade was in the doldrums; the J.B. Priestleys and the E.V. Appletons were searching for their fortunes in the more prosperous South.

By 1930, the Society's fortunes were improving. A well-organised recruiting drive was led by Dr J. Hambley Rowe, a veteran who had lost none of his enthusiasm, and Wilfrid Robertshaw now, after nine years' membership, Secretary and one of the Society's most vigorous workers. By 1939, membership figures had reached 215. The records were beginning to note the activities of the stalwarts of the forties and the fifties, among them E.E. Dodd, John La Page and Wade Hustwick, secretary from 1934 to 1944.

More recent activities

By the thirties, in fact, the city was entering a new phase of physical and social change. Several new roads were opened to accommodate adherents to the new form of transport - the motor car. Several new schools were built, and a start made to tidy up those parts of the city centre cluttered up with ugly and shabby commercial buildings. The process accelerated after 1945. Many of the landmarks of the Victorian city and the characteristics of its environment disappeared. Both the administrative structure and the regional authority of the borough which had been created in 1847 were transformed. In the circumstances, it was to be expected that interest in the local past would be stimulated. This was reflected in the remarkable increase in the membership. In 1953, just before the television era reached popular proportions, the number reached 322, and, although this figure could not be maintained, it stood at well over 200 until 1975.. There were, inevitably, specific difficulties of administration and organisation. Post-war inflation meant that subscriptions had to be raised to fifteen shillings in 1954, to £1. ls. in 1966, to £1.25 in 1973, to £2.00 in 1975 and to £3.00 in 1977.

The re-formation of the city centre in the 1960s, and the destruction of the admirable Victorian building, the Mechanics Institute, led to the Society's loss of what had almost become a permanent home. After a short period of trial and error, it settled at the new Bradford Central Library, where all its lectures are now held and where its valuable and extensive collection of books, pamphlets and other materials of interest to the local historian and antiquarian is housed. We think it should be recorded that a good deal of the work and the responsibilities of this period fell on the three men who since 1949 carried out the duties of secretary: G.N.T. Baxter, 1949 to 1956; J.B. Hustwick 1956 to 1966, and J.G.B. Haigh, (the President in 1977-78) from 1966 to 1977.

The Society maintained the high level of its contribution to the cultural life of the city. Lectures and excursions were well attended. The lecture programme became, as a matter of policy, a combination of local history and more general topics. In it has been reflected a welcome revival of interest in the immediate past, with such lectures as G. Firth's 'The Bradford Worsted Trade', J. Ayres 'Victorian Architects in Bradford', and J. Roberts on the crisis of the water supply in 19th century Bradford. The Society also continued to fulfil its responsibilities in questions of preservation. In the late 1930s, Heaton Royds had been protected through its intervention. John Smith's Tadcaster Breweries was persuaded to 'assist the Society in the preservation of the "Old House at Home" at Little Horton; and, when, at last, the City Corporation began to take the problems of Town Planning seriously, the Executive took up the question of ancient buildings with them and was allowed a representative on the Town Planning Sub-Committee. In 1943, a list of buildings in Bradford which ought to be preserved was supplied to the National Buildings Record, and the Corporation was asked to take up the matter of preserving Tong Hall and Tong Village. In 1951, after an annual dinner at which the Earl of Rosse made an appeal on behalf of the National Trust, the Society undertook to set up a joint committee of Keighley Corporation, the National Trust and its representatives to administer East Riddlesden Hall. Between 1956 and 1959 and again in 1973, the Aireborough Urban District Council was given a great deal of help in compiling and maintaining the list of buildings of historical and architectural interest required under the Town and Country Planning Act (1947), More recently, the Society lent its support to the Kirkgate Market Preservation Committee, the Paper Hall Preservation Society, and was also very active in its efforts to save the Mechanics Institute.

Some recent contributors to the Society's work

In 1949, one of the Society's members. Mr. R.R. Ackernley presented a collection of ancient domestic stained glass to Bolling Hall Museum. The annual report for that year reads:

This gift which has been made ... through the Society will be the means of replacing in Bolling Hall glass which was there prior to 1825 ... The glass is of high quality. The heraldic glass alone forms a series which any city might count itself fortunate to possess. but here it gains added value from the fact that most of the coats of arms are those of connections of the Bolling and Tempest families. owners of the Hall down to three centuries ago. By his generous action. Mr. Ackernley has placed the city of Bradford in his debt and the Society is proud to be associated with the gift.

In 1951, the seven hundredth anniversary of the granting of a Market Charter to the Manor of Bradford was commemorated by the presentation of a plaque to the Cathedral. The plaque was a reproduction of a scarce old print which depicted the 'two sieges of Bradford in 1642 and 1643 when the Parish Church Tower was hung with wool-packs to protect it against the cannon fire of the besieging Royalist Army'. Alderman Horace Hird. Lord Mayor of Bradford in that year and President of the Society. put forward the proposal and the cost was met by subscriptions raised among the members.

As had always been the case, the Society included in its ranks a number of men and women who were active and important local historians and researchers. Most of them contributed in one way and another to the literature and other material available. Mrs. Ivy Holgate had a substantial collection of old views, photographs and slides. Alderman Hird carried on where William Cudworth had left off and completed the story of the development of the Corporation after 1886 in How a City Grows. He also published two collections of essays, Bradford Remembrancer, and Bradford in History. The first is an important series of biographical accounts of Bradford men and women whose careers have not previously been recorded in any detail. The second deals with a number of lesser known events in the history of the locality from Celtic times practically to the present day. John La Page, President between 1940 and 1946 and Secretary in 1947 and 1948, (a man who has collected many honours in the field of local studies. including the distinctions of F.S.A., F.R.G.S., and F.R.H.S.), wrote the Story of Baildon. Wade Hustwick was a regular contributor both to the Bradford Telegraph and Argus, and The Journal of the Bradford Textile Society. The press cuttings collections of his articles are among the most regularly requested items in the Local History Section of the Bradford Central Library. E.E. Dodd, Senior History Master at Bingley Grammar School, and President from 1957 to 1959, had published in 1958 his Bingley, a Yorkshire Town Through Nine Centuries. More recently. John Roberts, in a collection of essays, Titus of Salts (ed. R. Suddards), has written what is widely regarded as the best summary of the history of the Bradford Worsted Textile Industry now available, and has published a meticulously researched pamphlet on the famous warehouse area of Little Germany. Councillor J.S. King also carries on the tradition with work on the Manor of Horton, the village of Heaton, and a history of the Bradford Tramways and Trolley Bus system. For many years, Edwin Mitchell has been a frequent contributor to the local press and local journals, and Gary Firth is the author of short illustrated Histories of Bingley and Bradford. J. Reynolds, one of the present editors, has published work on a number of aspects of Bradford history - the Independent Labour Party, trade unions, the Technical College, Undercliffe Cemetery and Saltaire.

Publications of the Society: The Editors

As a learned society, however, the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society has confirmed its reputation through the publication of its journal, The Bradford Antiquary. A decision was made at the start not to include anything except original work based on primary sources or the result of independent investigation. This principle has been maintained. During nearly a century of existence the journal has thus kept high standards of scholarship. Members in general approve the policy. One wrote in 1956:

I really think the Antiquary is better than ever, and I look forward to reading every issue ... (It is) all the more reason why the pages of The Bradford Antiquary should (continue to) contain only the results of original archaeological, historical and genealogical research since (the readers) are already acquainted with the contents of books on local history.

In the early days, it was intended that it should record the transactions of the Society - to make permanently available the information provided in members' lectures to each other. In more recent years, as the lecture programme has contained topics of more general interest, original work has been accepted from both members and non-members. In this way a much wider range of expertise has been tapped and a number of distinguished national historians have contributed - among them Professor (now Lord) Briggs, Master of Worcester College, Oxford and Professor J.T. Ward of Strathclyde University.

For any serious student of the history of Bradford and its locality, the journal is the starting point. Original articles of permanent value are to be found in every issue - and many of them have been used by historians writing more general historical studies. The first account of the great Bradford strike of 1825 (an event which is at present the subject of a doctoral thesis at the University of Chicago); a description of the development of the Leeds-Liverpool Canal; a fascinating account of the Bradford yeoman-clothier of the 17th century; a discussion of the origins of the Bradford Friendly Societies; a survey of Irish immigration in Victorian Bradford are among those which have been frequently cited in general works dealing with the origins and growth of English society. The first two volumes are particularly wide-ranging in their scope; taking in every period from pre-historic times up to the years just before the Society started its work. As with the lecture programme, in the middle years a great deal of attention was given to the 16th and 17th centuries. More recently, there has been a return of interest, also reflected in the lecture programme, in the more immediate past. Important articles have thus appeared on the Aire and Calder Navigation; and Professor Ward has provided biographical sketches of two 19th century factory reformers, Matthew Balme and Squire Auty. The latest issue continues the story of Bradford's labour history and follows the account of the 1825 strike with one on the other great strike in Bradford's history - the Manningham Mills strike of 1890-91.

It has always been the practice to include copies and transcriptions of important manuscripts as they become available. The second volume, for instance, contains transcriptions of the Parish registers and a copy of the Land Tax records for Bradford in 1704. Most important of all, it has the great Survey of the Manor of Bradford taken in 1342 on behalf of the Earl of Lancaster. This was discovered and transcribed by John Lister of Shibden Hall, Halifax, and gives a picture of the tenurial pattern of the manor in the first part of the 14th century. Used along with the Manor Court Rolls, which cover the years immediately afterwards, it is possible to establish an almost complete history of the life of Bradford in the decades of the Black Death. We hope to continue the practice with the publication of the Bradford Protestation Return of 1642 in the next issue.

Material of this kind was supplemented by the publication between 1914 and 1953 of a Local Records Series. There were four volumes, containing respectively, (i) transcriptions of wills, prcbate inventories, abstracts of bonds of inhabitants of the townships of Bingley, Cottingley and Pudsey (ii) West Yorkshire deeds (iii) the Court Rolls of the Manor of Haworth (iv) the registers of the Independent Chapel of Kipping in Thornton, Bradford. Every student of local history will recognise both the importance of the work and the demands it made on the compilers. The idea originated with W.E. Preston who did much of the early work. Clifford Whone was responsible for Volume III, and the whole venture was finally pushed thrcugh to a conclusion by Wilfrid Robertshaw with the assistance of Wade Hustwick. The financing of the project was particularly difficult; money was raised by subscription and the work issued only to subscribers. Its successful conclusion was due very largely to the determined enthusiasm of Wilfrid Robertshaw.

Editorial responsibility for The Bradford Antiquary was carried by four men between 1881 and 1972. They were William Cudworth (1881-1893), Charles Antoine Federer (1893-1907), Dr. J. Hambley Rowe (1907-1937), Wilfrid Robertshaw (joint editor from 1927 and editor from 1937 to 1972). They were all remarkable men - capable and vigorous. Their contribution not only to the Historical and Antiquarian Society but also to the life of the city was very great indeed.

William Cudworth, a Bradford man, was born in 1830 and died in 1906. He started life as an apprentice printer with William Byles and Sons in the offices of The Bradford Observer. By the 1860s he had joined the reporting staff and had begun his lifelong study of local history. His output was nothing short of prodigious. Over the years, in addition to his work for the Society, he wrote a series of descriptions of Bradford and its surrounding townships which have yet to be replaced as basic texts for the study of the town's development. His study of working class life in Victorian Bradford, The Condition of the Industrial Working Classes in Bradford and District (1887) is used constantly by historians today. As a young man, he had been one of the principal spokesmen for the Printers' union - the Bradford Typographical Society. He played a part in the development of almost everyone of the learned societies which emerged in Bradford in his time. He was probably one of the ablest men in the Bradford of his day.

Charles Antoine Federer was born in Switzerland in 1837 and died in Bradford in 1908. He had settled in Bradford as a teacher of modern languages in 1864, and in that capacity taught both at the Mechanics Institute and the Technical College for 35 years. Like Cudworth, he was a man of immense talent and wide interests. He taught six languages and was thoroughly at home in four more. On the one hand, he was one of the most distinguished students of linguistics in the North of England; on the other, he was one of the most active of social workers in the Guild of Help. His collection of local historical and literary materials, most of which is now deposited in the Bradford Central Library, was unrivalled in the district.

J. Hambley Rowe came from Cornwall and after training as a doctor, at Aberdeen, settled in Bradford in 1900. In addition to his private practice, he was consultant at the Children's Hospital, the Waddilove Samaritan Hospital and the Bradford Infirmary. His professional obligations included office in a number of local and national medical societies, and he also had a number of articles published in the important medical journals. Until his death in 1937 he was one of the Society's most enthusiastic workers. He helped with the library, arranged the syllabus of lectures for a number of years, organised many excursions and was President on two occasions. His own historical and antiquarian interests, like those of his predecessors were wide, though his preference seems to have been for the pre-history which drew him to his Celtic-Cornish origins rather than the history of the locality. It is impossible to do justice to the many other interests he pursued - the Bronte Society, the Bradford Literary Club, the Bradford Scientific Association. He gave his first lecture to the Society in 19O6 and his last in 1934. He was made a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1924, and in 1931 at the age of 61 took an M.A. degree by research.

Wilfrid Robertshaw, another Bradford man, spent his life in the Bradford Museums and Libraries service. His work there in the development of Bolling Hall and Cartwright Hall are an enduring contribution to the cultural opportunities of the district. It is, for instance, largely due to his efforts that the annual Spring Exhibition at Cartwright Hall has become one of the major events in the cultural life of the city. His connexion with the Society began in 1921 and for the next fifty years he remained a constant and tireless contributor to its success - as lecturer, excursion leader, researcher, writer, editor and administrator. He acted as secretary for a period and was President both in 1934-5 and again twenty one years later. As a writer, possibly the best article he wrote was his analysis of the Robert Saxton map of Manningham in l6l3. In addition to his duties as editor, he undertook the demanding task of completing the Local Record Series - being largely responsible for the preparation of Volume II and the completion of Volume IV.

The Bradford Antiquary, which first appeared in 188l, has now begun its twelfth volume. Altogether, during the hundred years of the Society's lifetime 56 parts have been issued. For a number of years, when printing costs were relatively low, the journal was issued every year. At other times, it has appeared at roughly twoyearly intervals, with only two comparatively long gaps; one between 19l9 and 1927 when only one issue appeared, and the other between 1972 and 1976. It has been a remarkable performance. The Bradford Society, unlike many others, has always been completely dependent on its own resources. It has had no wealthy patrons and has had help but rarely and meagrely from public bodies and institutions. Given the inflated cost of present-day printing, the financial problems associated with continued publication are among the most important which the Society has to face in the future.

Conclusion and a glance at the future

Yet the demand for a journal like The Bradford Antiquary is probably greater than it ever was. The amount of research done in local history has multiplied during the last three decades, and outlets for the publication of its results are always needed if the work is to have more than personal value. A new sort of social history is developing which adds a new dimension to the study of history - a social history which is not so much a bibliography of social events as a study of the way in which societies emerge, develop, knit together, disintegrate and are reconstructed. (An aspect of this work of particular relevance for Bradford is the attention given to the examination of urban-industrial societies in the 19th and 20th centuries). In this context, the study of history at the local level has become of central importance, and its wide dissemination a cultural necessity.

It is not, however, simply a question of providing for the cultural enrichment which comes from an understanding of the immediate environment. There is, it seems, a need to establish the bases of social identity again and to discern the new patterns of the expected future. An eminent historian, speaking about the role of history in education, has recently remarked, 'Everyone enters the future looking backwards. There is nowhere else to look. Even the most fanatical futurologist must accept this. His predictions can be nothing but ingenious extrapolations from perceived historical trends.' The rapidity of economic, social and political change in the lifetime of a generation means that we have to re-examine our grassroots in the light of our own experience. Thus the study of history at this level - not only the biographies of the rich and powerful or the story of formal institutions, but the genealogical connections of ordinary families, the life of the terraced streets and the suburban estates, the churches, chapels, clubs and societies which ordinary people created for themselves - transcends the parochialism of which it has frequently been indicted and becomes the warp and weft of new and more relevant general ideas about ourselves and the world.

An indication of its importance is the growing professionalisation of much of the work. A number of agencies now share the interests and the responsibilities which in 1878 such organisations as the Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society maintained alone. In almost all the institutes of higher education, the history departments (including those in Bradford) provide courses in local history. A great deal of postgraduate work is concentrated on it. University extra-mural departments and the Workers' Educational Association run regular classes which are among the most popular in their programmes. The Libraries and Museums offer special services and facilities. The subject forms an essential part of almost every School history syllabus. In Bradford, the Education service has its own Forster Society to promote research particularly, but not exclusively, in the field of education history.

The Bradford Historical and Antiquarian Society has reason to be proud of its contribution to these developments. But for the pioneering activities of its members in publishing their studies and preserving documents and other materials now in the custody of the Libraries and the Museums Services, it would have been very difficult even to start much of the recent work about the history of Bradford. The future role of the Society can be just as important, for the objectives laid down in 1878 are as relevant today as they were a century ago. There is a great deal still to uncover and much to re-examine. The possibilities of local archaeology, particularly in the medieval period, are by no means exhausted. For the seventeenth century, there are untranscribed manorial records and tithe surveys which await analysis, and from the eighteenth century, the Quarter Session records, for instance, contain a mass of unused material. Above all, we should keep constantly in mind the intention of our founders to document the recent past. As Bradford changes from the highly concentrated urban-industrial community of the nineteenth century to become, in the twentieth century, the centre of a sprawling industrial and residential conurbation, both its topography and its social structure are being altered as profoundly as they were between 1830 and 1880. At the same time, while the living record disappears, the wealth of information opened up for study about the nineteenth and twentieth centuries increases weekly. We have an obligation to see that it is properly documented. In all this, the Society still occupies a unique position. Its lectures and excursions provide a friendly meeting place for men and women of widely differing experience who have a common interest in the study of the past. Free from the bureaucratic entanglements of registers and formal syllabuses, they offer a regular forum for the dissemination of new ideas and fresh information. The Bradford Antiquary, possibly in a modified format, will continue as the permanent and scholarly record of the studies which are being made on the history of the locality.

Presidents of the Society

| 1878-1882 | Thomas T. Empsall | 1931-1932 | Eldred Oliver | |

| 1882-1883 | George Ackroyd | 1932-1933 | Francis V. Gill | |

| 1883-1896 | Thomas T. Empsall | 1933-1934 | Ernest Cummins | |

| 1896-1897 | J. Norton Dickons | 1934-1935 | Wilfrid Robertshaw | |